Hi pt1, Alex, & all,

pt1 wrote:I'm not quite sure how the quotes relate to the issue of right view practically. What I mean is - if we try to consider the issue practically, in particular your points 1 and 3 (dhamma theory and two truths), then imo we have to look at how insight (in essence, an instance of right view) is described to happen.

Where I think we would disagree is on what exactly is the right scholarly explanation of the experience of the individual characteristics (which according to Vsm is in fact what's referred to as sabhava or individual essence), right? So, while I think we agree in terms of practical experience (a and b), we are most likely to disagree on how exactly to define that experience in philosophical/scholarly terms (c), right? Anyway, I just thought it'd be good to clarify this before going further with the discussion.

Ascertaining right view is essential to practice as it relates directly to the development of vipassanā. Firstly, according to the suttantika stages of gradual training, the development of vipassanā has to eventually be conjoined with samatha in jhāna. This includes empirically and directly experiencing the momentary flux of pītisukha while remaining in jhāna. Specifically, this momentary flux is the characteristic of alteration while persisting (ṭhitassa aññathatta). As such it is an aspect of anicca. And so after emerging from the first or second jhāna one can be confident that even this incredible, expansive, even euphoric experience of non-sensual pītisukha is incapable of ever providing permanent happiness. It is impermanent, and therefore unsatisfactory (dukkha) and not-self (anattā). It should be developed but not be clung to.

Eventually, as the gradual training progresses, and along with it the development of vipassanā and paññā, one will have renounced and relinquished enough acquisitions that they are able to drop all reference points and object-supports – no matter how refined – and taste liberation. This is designated as a measureless mind (appamāṇacetasa) which is unestablished (appatiṭṭha), featureless (anidassana), independent (anissita), etc.. In short, it has no object-support (ārammaṇa).

In sharp contrast to this suttantika development of gradual training, the Mahāvihāra commentarial tradition maintains that the refinement and mastery of the non-sensual rapture, pleasure, equanimity, etc. of jhāna isn’t necessary. One can proceed by engaging in vipassanā as a self-sufficient alternative practice of right samādhi.

Now this is where the commentarial view of paramattha vs. paññatti has practical implications on how one develops along the course of gradual training. In the context of ānāpānasati, for example, according to the paramattha/paññatti distinction, the object of consciousness during jhāna is the counterpart nimitta. This is considered to be paññatti and therefore one cannot develop actual vipassanā while remaining in jhāna. So jhāna is, in this sense, marginalized.

Also very relevant to how one’s view has practical implications concerning the development of vipassanā is the commentarial theory of radical momentariness (khaṇavāda). Instead of attending to the empirical alteration while persisting (ṭhitassa aññathatta) of the actual, refined apperception of rapture and pleasure born of seclusion (vivekajapītisukhasukhumasaccasaññā) while remaining in the first jhāna; the very adherence to the view of the theory of momentariness superimposes a conceptual filter upon one’s empirical experience, which in the context of vipassanā is now interpreted as a momentary samādhi. Here, instead of the empirical experience of alteration while persisting (ṭhitassa aññathatta), one interprets their experience in terms of rapid momentary arising (uppāda), duration (ṭhiti), and dissolution (bhaṅga).

Moreover, by combining the theory of radical momentariness with the stages of insight gnosis found in the Paṭisambhidāmagga, the commentarial tradition has embedded this theory into the very structure of the development of vipassanāñāṇa, as well as the noble path and fruition.

And so as a result of ~600+ years of historical accretion (~2200 years of accretion if the modernist Burmese vipassanā interpretation of vipassanāñāṇa differs in any way from the Visuddhimagga), we now find well intentioned practitioners working themselves into something of an existential tizzy by interpreting their experience of the contemplation of dissolution (bhangānupassanāñāṇa) in terms of radical, momentary dissolution and cessation (this being just one example).

Add to this that the Mahāvihāra commentarial tradition has no way of accurately accounting for the liberated mind of an arahant, because for abhidhammika-s consciousness is always intentional – it always has to have an object support. Therefore nibbāna was smuggled into the dhammāyatana and dhammadhātu as the object of a supramundane, yet still fabricated, mental consciousness. And the cognition of this ultimately existent unconditioned element must necessarily be devoid of all other ultimately existent fabricated phenomena.

None of the above mentioned Mahāvihāra commentarial developments can be supported by a careful and objective reading of the Pāḷi sutta-s. If one is sensitive to the historical development of the Pāḷi tradition, and investigates these issues objectively with an open-minded and unbiased approach, they should be able to see this for themselves. The commentaries have not only rerouted the development of right meditation, they have completely redrawn the entire map. This has very significant and practical implications for anyone practicing the dhamma. As Retro said on another thread:

retrofuturist wrote:I accept there's something admirable about trying to find common ground, but from my perspective it's not just a case of "rivaling terminology" but "rivaling views". That is, specific aspects of each set of views which are either explicitly or implicitly incompatible.

Earlier, Geoff quoted this, from Ven. Ñāṇananda's Concept and Reality In Early Buddhist Thought, p. 87:

Lists of phenomena, both mental and material, are linked together with the term "paccayā" or any of its equivalents, and the fact of their conditionality and non-substantiality is emphasized with the help of analysis and synthesis. Apart from serving the immediate purpose of their specific application, these formulas help us to attune our minds in order to gain paññā. Neither the words in these formulas, nor the formulas as such, are to be regarded as ultimate categories. We have to look not so much at them as through them. We must not miss the wood for the trees by dogmatically clinging to the words in the formulas as being ultimate categories. As concepts, they are merely the modes in which the flux of material and mental life has been arrested and split up in the realm of ideation....

Now, what he is saying here, isn't just a question of terminology... it's a radically different concept of what a "dhamma" is. (If accepted) it effectively renders the entire objective/standardised foundation upon which the Abhidhamma is built, obsolete. It says that a dhamma is that which is "arrested and split up", formed (sankhata), conditioned by ignorance, by the individual. It does not unconditionally exist, nor is it "ultimate", nor is it an objectively existing object which innocently presents itself to the citta for investigation by panna... rather it is just that which the individual has ignorantly bracketed and falsely attributed "thingness" to - no more, no less. In other words, dhammas are the product of ignorance. All those carefully tabulated lists of dhammas are just mental constructions, conditioned by ignorance.

Try as you like, but I suspect such fundamentally different foundations on such a pivotal issue, cannot be overcome simply through "terminology". The gap is incredibly wide.

pt1 wrote:I'm not sure if you'd prefer to keep the discussion here strictly in scholarly terms, so perhaps I should keep the practical aspects of the discussion confined to the original samatha vs vipassana thread?

It’s a good idea to keep it here, as it is absolutely relevant to this discussion of right view.

Alex123 wrote:One can't escape something through lack of knowledge or lack of discrimination.

So you agree that the individuation of particulars requires discrimination.

Alex123 wrote:Now for intellectual theorizers, where they use logic, concepts and convincing wordplay, of course all require recognition & definition. But experience is one thing, and how we call it is another. Unfortunately a lot of logic (which may be convincing!) is the latter, play with words.

As Ven. Bodhi, Ven. Ñāṇananda, and others have pointed out, the commentarial authors are agile wordsmiths who have seen fit to contrive fanciful etymologies and interpretations which stretch the limits of language to something of an extreme. On the other hand, the few suttantika-s who I’m familiar with are quite straightforward for the most part.

Alex123 wrote:Of course the atta should not be understood conventionally and one shouldn't misunderstand it and proceed to refute something due to this misunderstanding.

The Visuddhimaggamahāṭīkā citation is merely a conventional description. There is nothing there to refute

per se. It's just one of many examples of exegesis which serves no soteriological purpose.

Alex123 wrote:For sure the Buddha did have teachings on momentariness

None of the sutta citations you have supplied are referring to the theory of radical momentariness.

All the best,

Geoff

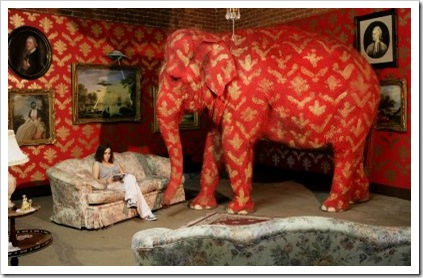

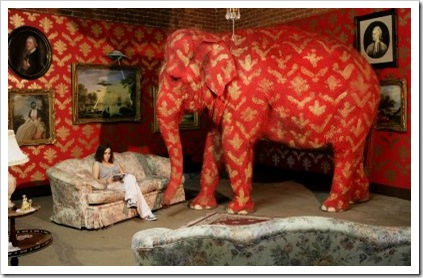

BTW, I have gone against my own inclinations by starting this thread. I have no intention of trying to change anyone’s opinion on these issues. I know that even questioning these matters which people feel deeply invested in can elicit anything from emotionally charged reactions to the outright denial of the specific issues involved. I wish that weren’t the case. Nevertheless, the elephant in the living room can be difficult to ignore.